So Walt Shipley, one of the most driven and inspired climbers I've ever had the pleasure to climb with, had mysteriously vanished from his main stomping ground, Yosemite Valley. During a work-day at A5 Adventures I get an out-of-the-blue telephone call from Walt: he's just been on an incredible solo binge in the Red Rocks, Nevada (which included multiple 5.10 Grade V's in a day, on-sight 5.11's, etc.), and is heading east to Flagstaff for a visit. It's just the opportunity I've been waiting for: a true go-for-it partner to team up with for some of the outrageous desert spires that I've been scoping since moving into the area.

As soon as Walt arrives, I propose an adventure: an ascent of Organ Rock, a remote 500' high fin of rock located in the depths of the desert. And without further ado, we were on the road. Walt then revealed the true motivation of his travels: a recent break-up with a waitress from the Mountain Room Bar in Yosemite. "I'm never going back to the Valley," he'd say. He sounded off endless sour details of the jilt, and I could see that he was pretty twisted. The only consolation I could come up with was, "well, what do you expect, special treatment?". I could see that Walt was in fine form for a desperate life-or- death adventure.

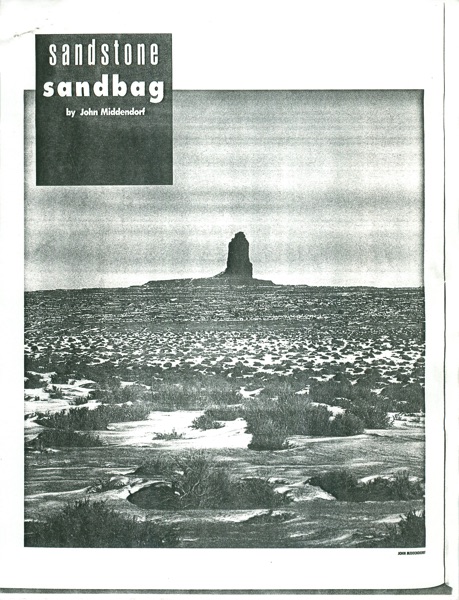

We arrived in the vicinity of Organ Rock at night. I was familiar with the complicated 4WD navigation to the base from several reconisances initially intended as solo efforts. Faint roads led to sandy washes which led to even fainter roads. After a few close calls with getting lost and stuck, we spot Organ Rock as a dark spot on the horizon. Satisfied with our progress, we pull the car into a deep wash and camp for the night.

Early the next morning, we continued navigating, and were able to drive almost to the base. Even the most remote areas of the Indian Reservation are populated by Navajo families in hogans, who undertandably dislike trespassers. Smooth passage in the Navajo backcountry is the combined result of discretion, luck, and flawless routefinding. We both understood that our presence on the "Res" was both illegal and disrespectful, but the lure of one of the last unclimbed desert spires overwhelmed the potential ill-consequence to life, limb, property, and kharma.

Organ Rock is the loosest of loose spires. By comparison, the Fisher Towers seem solid. Organ Rock Shale, a major geological strata, is named for Organ Rock. It seemed incredible that it had never been climbed. Eric Bjornstadt and Fred Beckey first spotted it from their ascent of Eagle Rock Spire in 1970, and spent days trying to locate it. When they finally found the area, they were enticed into climbing a more elegant spire to the south (Jacob's Ladder), and left Organ Rock to its own.

At the car, we debated over the rack. I opted for a full-on aid arsenal, but Walt convinced me that our initial recon should only include a light free rack. We hiked around the entire spire, and saw several possiblilities, mainly loose- and dangerous-looking chimney systems. But one line (the steepest) stood out in particular: an awesome overhanging crack system up the center of the SW Buttress. We agreed to give it a go.

"It's an aid line, Walt", I insisted with the intention of heading back to the car to organize the nailing gear.

"Hang-on a minute, this first section will go free", Walt responded, and geared up for the lead despite my protests based on a broader experience with desert sandstone. Vertical venturing on the loose stuff with nothing but a cragging rack seemed nuts to me, but there's no stopping Walt once he gets that amped gleam of pure inspiration, so I consented to the belay. A 5.10 loose offwidth roof made for an impressive first pitch. The second pitch went at 5.8, and I arrived at a ledge at the base of the main overhanging crack system. The belay consisted of two slung mounds which a few kicks could have cut loose. It was looking pretty serious.

A Navajo sheperdess, tending a flock of sheep, wanderered around nearby while we were climbing. Hearing our clanging of gear and mistaking it for a lost sheep's bell, she rode her horse up to the base. At one point she was directly below us, forcing us to freeze in place for what seemed like a long period of time. But she never once looked up, and eventually rode off puzzled.

Then the real nightmare began. Twenty feet up on the third pitch, Walt realizes that he's committed and started to moan about the climbing. It's death. The crack, though handsize, consisted of multiple loose layers of caked sand and made jams incredibly tenuous. The characteristic horizontal grooves of Organ Rock Shale creates steep bulges every five feet, and required awkward mantles on fragile shelves which would cut loose as often as not. Fractured flakes outside the crack were the most secure holds, yet not even the best would hold more than a 50 pound pull. Each move required an incredible balance between at least three carefully- chosen points of contact, otherwise the hand and footholds would crumble. The protection was non-existent: not only was the rock so friable that camming devices were useless, but even an Hexentric in a constriction would have obviously ripped through the soft rock. Nothing would have held body weight; lowering off was out of the question and the moves were far too tenuous to downclimb. A fall would have ripped the pitch and the belay.

The purest of psychotic climbing: Walt was in his element. Hundreds of pounds of sandstone broke off, but not Walt. I was glad that it was Walt's first desert sandstone experience, for his lack of expectation gave him a base level of confidence. He probably imagined that all desert climbing was as desperately loose. Any doubt, hesitation, or momentary lapse of concentration would likely have killed us both. After several hours of tense climbing, Walt called, " Off Belay!", and some blood returned to my knuckles.

Following the pitch, I found every move to be 5.9 or 5.10, and several times I almost fell, overweighting holds which were sent flying. The pitch, a full rope length, overhung about 10 feet in all. Walt's hanging belay in an alcove consisted of several slung television-sized chockstones which rocked and pivoted precariously as I climbed over them on the next pitch. I could have easily trundled the whole lot.

After two more easier pitches with non-existent belays, we reached the top. We relaxed on the summit and basked in the sun, amazed and relieved by our survival. As an offering to the desert spire gods, I left some Camels and matches in a waterproof container on top. After a while, Walt's memory of the waitress, mercifully displaced by the intensity of the climb, faded in. Sensing the beginnings of another tirade, we instead began our descent.

We placed no bolts or pitons, and all of our rappels consisted of slings around knobs or natural chockstones. It was indeed, a perfect desert ascent. We named it "Bite Harder", after a fine Yosemite camp cartoon. Grade III, 5.10XXX.

A feast of Navajo Tacos in Kayenta sealed the adventure.